One of the hardest things I had to deal with while serving in the Israel Defense Forces was learning to keep the faith and staying upbeat in touch times. I hardly spent enough time in Israel as a kid to feel a comfortable connection with the country, and serving in the military albeit by accident, was a world away from my comfortable American existence.

Although I didn’t quite realize it at the time, each time I was up against an obstacle in the IDF, I behaved in the same manner: I filled my head with “what-ifs” until I couldn’t fill it up any further and when I didn’t have any other place “to go,” I started to think positively.

Now, almost twenty five years as I write an entertaining story behind the battle, I understand now how those early lessons of positivity transformed me and I’d like to share those early lessons now with you.

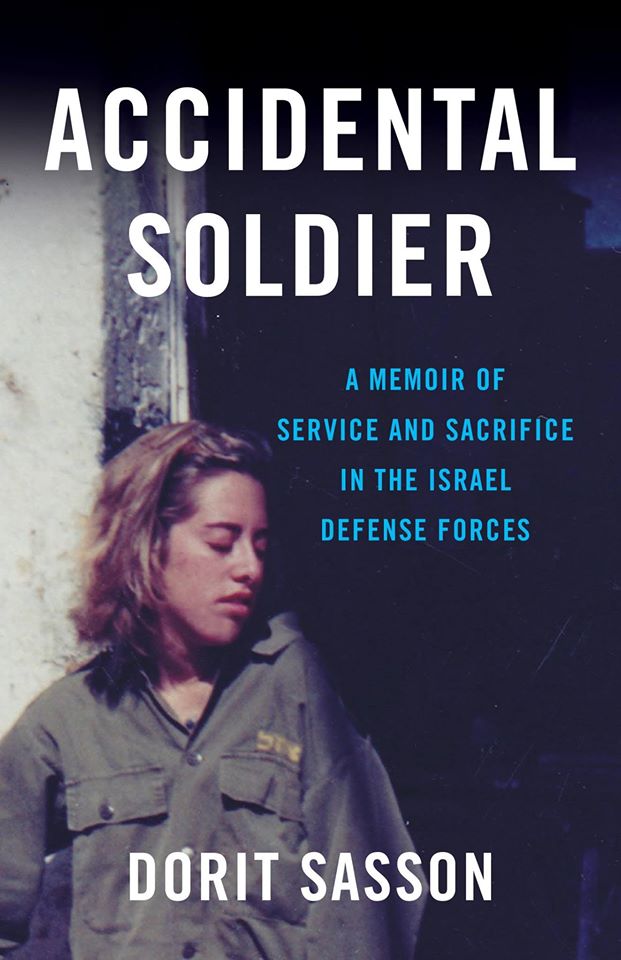

1. I learned to see the gift in every moment. Now, I know what you’re thinking. That’s an adult talking. An 18 year old is often pulled in so many directions that it’s hard to stay positive. Who knows what one wants at age 18? There’s so much peer pressure. (But I couldn’t leave the army. Volunteering for the IDF was an “accident,” thus the title of my memoir.) So I learned to thrive with the conditions I had and that meant finding a tune to dance to that “positive melody.” Whether I was made to feel stupid because I didn’t know I was walking in “mine” territory due to a language barrier or appeared fifteen minutes late for an army exercise because I was taking a shower, I was often ridiculed and scolded mainly by my fellow garin female members and other officers. When I realized I had to change, I stopped victimizing myself and eventually, stepped up to the calling as a leader. This is what my memoir is all about — the journey of transformation.

1. I learned to see the gift in every moment. Now, I know what you’re thinking. That’s an adult talking. An 18 year old is often pulled in so many directions that it’s hard to stay positive. Who knows what one wants at age 18? There’s so much peer pressure. (But I couldn’t leave the army. Volunteering for the IDF was an “accident,” thus the title of my memoir.) So I learned to thrive with the conditions I had and that meant finding a tune to dance to that “positive melody.” Whether I was made to feel stupid because I didn’t know I was walking in “mine” territory due to a language barrier or appeared fifteen minutes late for an army exercise because I was taking a shower, I was often ridiculed and scolded mainly by my fellow garin female members and other officers. When I realized I had to change, I stopped victimizing myself and eventually, stepped up to the calling as a leader. This is what my memoir is all about — the journey of transformation.

2. I learned to trust myself. This was probably my most powerful lesson of being positive. When you’re at peace with yourself, you feel more positive about who you are and where you’re going. you don’t care what other people think or say.

I came from a household where I was conditioned to live in fear and also, fear Israel for the sake of honoring the status quo. At a breaking point in the army, I decided to finally ignore the outside voices and work with this group of foreigners and strangers without trying to “fix” them so I could be the best soldier possible.

Here’s a short sample to reinforce what I mean:

Chapter 17, Basic Training

There’s that one memory in basic training when I had kept to myself and didn’t give of myself. It happened once prior to a major inspection, a few weeks before our 28 kilometer march. We were gathering our guns and other supplies while officer Ayelet kept an eye out in between two tents: ours and the one next to us. Nobody really paid attention to her, but I did. Her round pale face was shadowed by her cap pulled forward which made her look actually tougher and much more forceful beyond her sweet demeanor.

The adolescent in me wanted to strike out. Why the fuck is she here? Why is she observing us? Why can’t she go perch somewhere else? If she’s tough, then I’ll be even tougher. I’ll ignore her. So there.

The result was that I showed my negative side the minute the bickering with the other girls became too much. I would lash out. That day I hadn’t slept that many hours and was even more irritable and cranky. I would fight the girls in my garin with force. I had no other way. This would be the only language they’d understand. I was tired of being victimized and picked on.

3. I learned to “do it scared.” The “do it scared” tactic almost always pushed me past my comfort zone, and from there, I would have to find a “new comfort zone.” It wasn’t the ideal way of replacing a negative thought, but it was the only way to “emotionally survive.”

3. I learned to “do it scared.” The “do it scared” tactic almost always pushed me past my comfort zone, and from there, I would have to find a “new comfort zone.” It wasn’t the ideal way of replacing a negative thought, but it was the only way to “emotionally survive.”

At this “new” emotional place, I would repeat the mantra that my officers would often tell me, “you can do it,” when they saw me at the breaking point. Eventually, I would find a way to trick my brain and believe it. So in short, “the do it scared” tactic was the only way for me to get over initial waves of fear because essentially, I had no choice. And when you have no choice, it’s truly amazing the things you can do beyond your dreams.

This “do it scared” tactic has stayed with me until today. Now at midlife as I write this memoir, I’ve done the “do it scared” tactic many times over whether I’m writing this memoir or building my business. The fear has served its purpose.

When you have no choice, you learn to make the most of every resource and situation that you’ve got and that includes developing a positive mindset. Not easy. But doable.

How has it been going in terms of developing a positive mindset – easy or not? What were some of your takeaways or lessons?

It can definitely be a challenge to stay positive all the time. In some ways, blogging has helped me in that area – knowing that I’m “on stage” in a way, with readers who can choose whether or not to bother visiting my blog again, keeps me looking at the positive side of things. Thanks for this thought-provoking post!

Yes, laurel, yes!

That was a beautiful read and inspiring. I love to see people turn tough situations into positive learning experiences. I always turn and look at my life and the things that could be and turn whatever negative into a positive.

Thanks so much, Cassandra!

Beautifully written and a tough situation handled well. Growing up in an environment of negativity, I lived in fear of disappointing someone, anyone, mostly my mom. I was in my 50s, married to my second husband, and moved 2200 miles away from everything I knew from childhood. My beautiful man taught me positivity. We are living in retirement now, and I am happy to say that when the going gets tough, I dig down deep and rather than “lose it” I manage to turn the difficult around fairly quickly. Can’t wait to read your book.