It’s the last day of Passover in Pittsburgh, on a special day called the Moshiach’s meal, a symbolic way of embracing the Messiah – the redemption, and I’m leaning against our porch door. My eyes are full of tears and I tell my husband who’s holding a box of matzah and grape juice that there’s no way I’m going to make it to our Chabad synagogue, less than a mile away. I’d be the only woman there. I’m already lonely and full of longing for Israel, our heart home where I lived for nearly twenty years.

He looks at me as if to say, “I understand.”

I say, “I don’t feel I belong here” loud enough for him and others on our quiet street to hear. But our phones have turned into metal for the past 48 hours and as practicing Jews, my longing has no digital release.

Passover in Israel is a very family-oriented holiday and our sacrifice to come to the States means my kids don’t get to visit with their Israeli aunts, uncles, and cousins. That all the Passover and sedar preparations feel like one big chore without family. Since the virus started, we haven’t really had any guests and our Israeli family has turned into a Facebook one.

But it’s not just on Passover I feel these pangs of longing. They occur in the least unexpected way: trying to get through the Israeli consulate or hearing an Israeli writer suddenly switch from English to Hebrew reminds me of how challenging it is to straddle two very different worlds. When I see my Israeli neighbor walking down the street, I don’t hide as I used to do when I first arrived in Pittsburgh. Our mother tongue binds us, but still, I know that the minority status we carry makes it even easier for us to be swallowed by American life, English. And at worse, feel alienated even from each other.

“Maybe you had to leave in order to really miss a place; maybe you had to travel to figure out how beloved your starting point was.” -Jodi Picoult (Handle with Care)

When we left Israel in 2007, I didn’t know how long we’d be leaving. I didn’t know if we were ever coming back. All I knew was that I was fed up trying to find a professionally paying job for my husband, Haim. It was heart-breaking that we had no choice but to leave. But this is the Israel I knew well for the last 20 years and left – overly dramatical, and unfair to the hardworking and decent blue-collar class we had become. Our kibbutz it felt, had let my husband down and at the time, it felt there was no-one who stepped in to say, “I’m sorry” or “let me help again. Is there something we can do to get you to stay?”

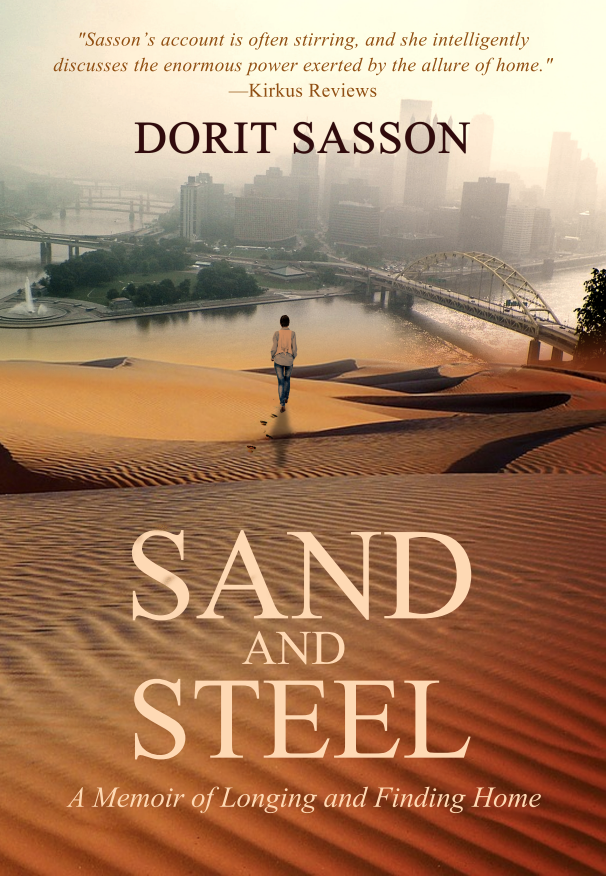

In my upcoming memoir Sand and Steel: A Memoir of Longing and Finding Home, I explore the “why” behind leaving and the implications they have on identity and language.

Sand and Steel: A Memoir of Longing and Finding Home officially releases August 3rd, but you can pre-order your copy here.

Connect with Dorit